|

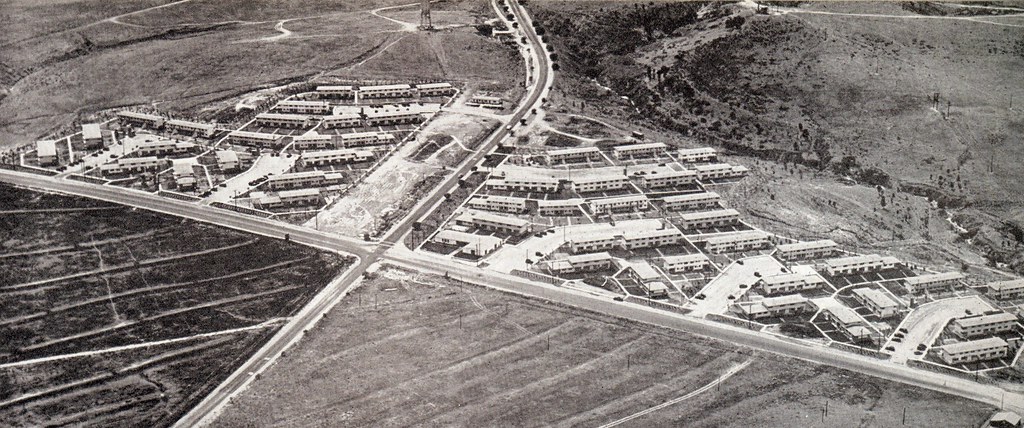

| Sunnyside Gardens, Queens, New York |

"Though our means were modest, we contrived to live in an environment where space, sunlight, order, color - these essential ingredients for either life or art - were constantly present, silently molding all of us."

- Lewis Mumford, writing about his experiences living at Sunnyside Gardens, New York, Clarence Stein’s earliest Garden City community. [i]

After living at the Village Green for over six years, I can personally attest to the transformative powers it has, successfully bringing people together. I believe that most people who live in the Village feel equally passionate about the place we all call home - and I’ve seen that same pride and passion in the residents of Wyvernwood, as they fight to save their community.

Make no mistake about it, though, these transformative powers, and the feelings of pride they instill, are no accident, but are the result of a design carefully and expertly engineered to function in precisely this way. To fully understand why communities like Wyvernwood and Village Green still work as well as they do, even with many of their planned amenities removed, one must understand what architect and urban planner Clarence Stein’s vision was for these communities, which were created using both the art and science of design to be a new paradigm for modern, planned housing. Though Clarence Stein wasn’t directly involved in the creation of Wyvernwood, it was developed using Stein’s principles, and as such, is a direct product of his ideas and philosophies - as are all of the Southern California Garden Cities.

All this week on the Baldwin Hills Village blog, we’ll take a look at the designers who created Wyvernwood, and describe the history of this fine community, as well as the current fight to preserve it. The complete series of Wyvernwood posts can be found HERE

In the first half of the 20th Century, the designers working on communities like Wyvernwood believed that they could use new concepts in housing as a medium to express, and even shape the values and well-being of the community; that providing residents with easy access to fresh air and open green spaces, with provisions for recreation and social interaction in them, would help create strong community bonds and a sociability which would enhance and enrich their lives in ways they wouldn’t normally be able to achieve in a city apartment, or often even in a suburban situation.

During these years, forward-thinking city planners, architects and landscape architects began working together to create a new idea of urban community, as they had seen in modern housing “the chance of creating… brave new communities – uncluttered, throbbing with new life and vigor, beacons of urbane living.”[ii]

Leading this revolution in modern housing was renowned urban planner Clarence S. Stein. Largely through his farsighted guidance, the architects, planners and landscape architects of this movement believed that entirely new communities, using Garden City principles, could be built on open, undeveloped land just outside city limits, surrounded by greenbelts, but linked to one another by public transport or highways; at the same time, the slums and decay of the existing inner cities would be rebuilt, reorganized and improved using many of the same principles. Each would be integrally and organically related to the overall community, and to each other; and with carefully planned attractive shared open spaces, it was hoped that their surroundings would subtly mold and direct people toward socially progressive aims and greater involvement in the community.

Influential architecture critic Lewis Mumford wrote that the Garden City communities of Clarence Stein and his partner Henry Wright “dared to put beauty as one of the imperative needs of a planned environment: the beauty of ordered buildings, measured to the human scale, of trees and flowering plants, and of open greens surrounded by buildings of low density, so that children may scamper over them, to add to both their use and their aesthetic loveliness.”[iii]

In the first half of the 20th Century, the designers working on communities like Wyvernwood believed that they could use new concepts in housing as a medium to express, and even shape the values and well-being of the community; that providing residents with easy access to fresh air and open green spaces, with provisions for recreation and social interaction in them, would help create strong community bonds and a sociability which would enhance and enrich their lives in ways they wouldn’t normally be able to achieve in a city apartment, or often even in a suburban situation.

During these years, forward-thinking city planners, architects and landscape architects began working together to create a new idea of urban community, as they had seen in modern housing “the chance of creating… brave new communities – uncluttered, throbbing with new life and vigor, beacons of urbane living.”[ii]

Leading this revolution in modern housing was renowned urban planner Clarence S. Stein. Largely through his farsighted guidance, the architects, planners and landscape architects of this movement believed that entirely new communities, using Garden City principles, could be built on open, undeveloped land just outside city limits, surrounded by greenbelts, but linked to one another by public transport or highways; at the same time, the slums and decay of the existing inner cities would be rebuilt, reorganized and improved using many of the same principles. Each would be integrally and organically related to the overall community, and to each other; and with carefully planned attractive shared open spaces, it was hoped that their surroundings would subtly mold and direct people toward socially progressive aims and greater involvement in the community.

Influential architecture critic Lewis Mumford wrote that the Garden City communities of Clarence Stein and his partner Henry Wright “dared to put beauty as one of the imperative needs of a planned environment: the beauty of ordered buildings, measured to the human scale, of trees and flowering plants, and of open greens surrounded by buildings of low density, so that children may scamper over them, to add to both their use and their aesthetic loveliness.”[iii]

Clarence S. Stein (1882-1975), one of the twentieth century’s most profound visionaries, led groundbreaking innovations in urban planning. Though trained as an architect, he was also a persuasive writer. Born, raised and educated in New York, Stein was primarily considered an East Coast figure, though he did have strong and early ties to Southern California. After studying architecture at Columbia University and the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Stein returned to the United States in 1911, joining the firm of Bertram Goodhue in New York. Goodhue sent Stein to Southern California, where he worked as chief designer on several large-scale projects, including the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego, California, and the master plan and individual buildings for the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

Moving back to New York in 1919, he opened his own practice. In 1921, he began a long and fruitful collaboration with architect Henry Wright (1878-1936). This charismatic partnership would produce some of the most innovative urban planning in the history of the United States.

In 1923, at Stein’s initiative, the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA) was formed, in collaboration with Henry Wright, and other members including Lewis Mumford, Benton MacKaye, and Alexander Bing. The goal of this group was to “connect a diverse group of friends in a critical examination of the city, in the collaborative development and dissemination of ideas, in political action and in city building projects”

The RPAA had a profound influence on urban development through the prolific and effective writing of its members. More importantly, Stein and Wright spearheaded new and innovative ideas in community planning, starting with some private developments on the East Coast. These were inspired by Sir Ebenezer Howard, who had initiated the Garden City movement at the turn of the 20th Century in Great Britain, with his book “Garden Cities of To-morrow,” and also by modern German, Dutch and British large-scale housing of the 1920’s.

The first of these projects was Sunnyside Gardens in Queens, New York. Sunnyside Gardens, a seventy-seven acre low-rise development, was constructed from 1924-29. This was followed by Radburn, a much larger community in New Jersey, begun in 1929. “In these projects, Stein, Henry Wright and Alexander Bing rethought the basic social and environmental needs, as well as the financing and physical layout, of the American urban residential community; in so doing, they created new urban forms.”[iv] (an excellent blog about these communities here)

|

| Freedom from dangers of the automobile at Radburn |

Particularly at Radburn, Stein and Wright created a revolution in planning, which would truly deal for the first time with the problem and dangers of the automobile. Stein had written that what he hoped his communities would offer was “a beautiful environment, a home for children, an opportunity to enjoy the day’s leisure and the ability to ride on the Juggernaut of industry, instead of being prostrated under its wheels.”[v] At Radburn, “a community within a community,” automobile traffic was separated as much as possible from pedestrian traffic, and for the first time a largely residential “superblock” concept of planning was used. Radburn was followed in the 1930’s by more “towns for the motor age” - Chatham Village (Pittsburgh), Phipps Garden Apartments and Sunnyside (Long Island) and Hillside Homes (the Bronx). In addition to beauty and promotion of social life for their inhabitants, the basic Garden City principles developed by Stein and Wright, were:

- Superblock – large parcel with few or no through streets, which consolidated open green spaces for use by the residents;

- Specialized roads – all auto circulation on the perimeter – garage courts for storing of cars;

- Complete separation of pedestrian and automobile – tame the automobile – safer for children;

- Houses turned toward gardens and parks – this arrangement turned the structures outside in, placing the living room windows towards the green spaces;

- The park as the backbone – large green spaces dominate, rather than streets.

Stein and Wright’s philosophies were embraced by the government during the early years of the Great Depression, serving as the design standard for the public housing programs. Acting as a consultant on Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Greenbelt Towns program, Stein hoped that these initial steps would pave the way for ideal community planning at a much larger scale.

|

| Clarence Stein and his wife Aline |

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA GARDEN CITIES

Because of his innovations in urban planning on the East Coast, in early 1938 Clarence Stein was hired by the Housing Authority of the County of Los Angeles to serve as the consulting architect on its first two projects – Carmelitos and Harbor Hills. In August and September 1938, Stein travelled to California to meet with Housing Authority officials and the architects involved with the projects with whom he would work.

|

| Clarence Stein and the Carmelitos architects working on the site plan using wooden blocks, 1938 |

The first of these - Carmelitos in Long Beach, (Kenneth S. Wing and Cecil A. Schilling, architects; Ralph D. Cornell, landscape architect) - would provide 607 homes for families whose annual incomes ranged from $900 to $1,200 annually.[vi] The fifty acre site had eighty-seven buildings, arranged in such a way that ample parking was provided, but automobile and pedestrian traffic was kept as separate as possible. A backyard garden was provided for every family, and provisions were made for playgrounds, an outdoor nursery school, and other recreation areas for both children and adults.

|

| The site plan for Harbor Hills |

At the next community, Harbor Hills, (Reginald D. Johnson, Chief Architect; Donald B. Parkinson, Eugene Weston, Jr, Lewis Eugene Wilson, A.C. Zimmerman; Katherine Bashford and Fred Barlow, Jr, landscape architects - Johnson, Wilson and Barlow were later affiliated with Baldwin Hills Village), built on a captivating site overlooking the San Pedro Bay, only 27 acres of the 102 acre site was developed, because of several deep canyons and gullies. Buildings were grouped around large parking areas, which were fifty-four feet wide. Room was also provided for off-street parking for all tenants. The development followed the contours of the site, utilizing a chevron pattern to break up the repetition of the parallel rows commonly used in other housing projects, giving it a unique character.

A rather small housing development, with just 300 units in 52 buildings on 102 acres, provisions were still made for community equipment. Clarence Stein believed that creating larger developments would “have the advantage of being able to afford more adequate and varied community space and service. Therefore, wherever it is practical, it would seem advisable to organize public housing in developments large enough to supply community equipment that can be administered with maximum economy.”

|

| Children enjoy the spray pool at Harbor Hills |

Stein visited California in October 1941, and said “I visited both Carmelitos and Harbor Hills. I was delighted with the appearance of both of them. Harbor Hills in detail is, I think, one of the best projects in the country. Carmelitos is very attractive.”[viii]

During this time, Clarence Stein was also busy acting as consulting architect for Baldwin Hills Village. At Baldwin Hills Village, Stein’s tenets came together in their most fully realized form. Even more so than at his communities on the East Coast, in Southern California the region’s “necessary evil” – the automobile, and the car-centric culture that had grown up around it – had to be solved. The same year the Arroyo Seco Parkway opened - Southern California’s first freeway - the design team behind Baldwin Hills Village finalized their radically inspired plans to “tame the car.”

END OF THE HOUSING ERA

In the postwar years, returning veterans and their families caused the housing crisis to continue. Because Los Angeles was a port of dispatch and re-entry during the War years and immediately thereafter, more than seven million men and women who served in the armed forces had experienced Southern California, some for the first time. The allure of the location and climate was enough to beckon nearly one third of all out-of-state veterans back to settle in Southern California following the war.[ix]

As the housing crisis began to subside, acceptance for the idea of public housing waned in the years following World War II, as beliefs and philosophies evolved – private real estate became more desirable, and government housing was looked down on as a form of socialism – or worse, communism. The two emergencies (economic and war) of the prior decade and a half had waned, and so had the acceptance for affordable government subsidized housing, and even privately funded large-scale housing developments like Wyvernwood or Baldwin Hills Village.

The hope had been that these private housing developments would provide the urban model of “villages in the city” connected by public transport. But their innovative solutions to “taming the automobile” and fostering intimate social community within sophisticated, high-density urban settings was lost to the changing times when rapid, piecemeal real estate development and the profits it engendered swept these principles and opportunities aside. Stein’s vision for communities built on undeveloped land (like at Wyvernwood and Baldwin Hills Village), while the slums of the inner city were replaced with idealized communities (such as at Aliso Village or Ramona Gardens) never came to pass.

The returning veteran’s dream of possessing a free-standing house of his own, where he would raise his family, and cultivate his own plot of land, overshadowed the pursuit of communities designed with carefully planned communal gardens designed to create the “spirit of fellowship and cooperation.”See the complete series of blog posts about Wyvernwood HERE

[i] “Invisible Gardens,” Walker and Simo

[ii] “Making a Better World,” Don Parson, University of Minnesota Press - quoting architect and housing advocate Albert Mayer p.8

[iii] “Toward New Towns for America,” Clarence Stein, 1951, p. 18-19. (Liverpool: University Press of Liverpool)

[iv] “The Writings of Clarence Stein,” Kermit Carlyle Parsons, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998, p. xxiv

[v] “Invisible Gardens,” Walker and Simo, pr 46 – referencing Stein’s article “Dinosaur Cities,” Survey Graphic 7 (May 1925), p 134-138.

[vi] According to the CPI Inflation Index, $900-1200 in 1940 dollars calculates to about $14-19,000 in 2011

[vii] “Public Housing,” California Arts & Architecture, July 1941, p. 32

[viii] “The Writings of Clarence Stein,” Kermit Carlyle Parsons, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998, p. 423

[ix] “The Provisional City: Los Angeles Stories of Architecture and Urbanism,” MIT Press, 2002 Dana Cuff, p 54

Thank you for this series; very comprehensive and well-done. Your passion for V.G./B.H.V. and the ethos behind them is evident.

ReplyDeleteThis is great information. Thank you for researching, writing, and sharing your work on Wyvernwood.

ReplyDelete